The Challenges Facing Environmental Education in Transboundary Conservation

The Challenges Facing Environmental

Education in Transboundary Conservation:

Sharing the Experience of the Maloti Drakensberg

Transfrontier Project.

Elna de Beer

Social Ecologist – MDTP,

edebeer@golder.co.za

Ntombifuthi Luthuli

Senior Community Conservation Officer, eZemvelo KZN Wildlife,

luthulin@kznwildlife.com

Sandra Taljaard

Regional Co-ordinator: People and Conservation, SANParks,

SandraT@sanparks.org

Abstract:

Since its inception in 2003 the MDTP faced challenges of ensuring collaboration between multi level stakeholders which were disparate in nature and none more so than in the development of an environmental education programme aimed at the protection of globally significant biodiversity. Conventional community development approaches and processes such as Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) seemed inadequate to mobilize prior knowledge in a disparate environment. The open process framework embarked upon provided an opportunity to mobilize stakeholders to participate in the development of the MDTP enviro-picture which effectively became a mechanism/tool linking diverse resources to an array of activities and education outcomes.

Keywords: Transboundary conservation, challenges, open process framework, networking

INTRODUCTION

Existing approaches that relied heavily on awareness raising, attitude change and the romantic notion of behaviour change are challenged by international trends seeking more innovative approaches that can cope with the increasing realization that environment and sustainability issues are complex and that they involve interactions between the biophysical environment and other dimensions such as; political, social, technological, aesthetic and economic.

Transboundary conservation processes are complex and it challenges environmental education programmes to go beyond conventional approaches and consider orientations such as “open process” and “prior learning” in the development of education programmes.

This paper will focus on the process the Maloti Drakensberg Transfrontier Project (MDTP) in South Africa has engaged with in their attempt to face the challenges posed to environmental education in a transboundary conservation context.

WHAT IS TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION?

Over the last decade transboundary conservation has developed into a phenomenon that is not only internationally recognized but it is also challenging conventional approaches to conservation management. Recent history indicates an initial emphasis on transboundary protected areas which the World Conservation Union (IUCN) defines as “an area of land and/or sea that straddles one or more states, sub-national units such as provinces and regions, autonomous areas and/or areas beyond the limit of national sovereignty or jurisdiction, whose constituent parts are especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed cooperatively through legal and other effective means.” (http://www.tbpa.net/issues_04)

However, it was quickly realized that transboundary conservation extended beyond the conservation of biodiversity through protected areas. The Global Transboundary Protected Area Network recognizes that conservation across boundaries can include a wide variety of different approaches, linked by a common theme that they straddle international borders. As such, a typology of Transboundary Protected Areas based on the findings of an international workshop in 2003 hosted by the IUCN and the International Tropical Timber Organization was developed. (http://www.tbpa.net/issues)

The Typology of Transboundary Protected Areas can be listed as follows:

- Two or more contiguous protected areas across a national boundary

- A cluster of protected areas and the intervening land

- A cluster of separated protected areas without intervening land

- A trans-border area including proposed protected areas

- A protected area in one country aided by sympathetic land use over the border.

It is hoped that as the practicing of transboundary conservation will continue, so will the range of approaches to managing these areas across borders continue to expand.

Internationally many transboundary conservation initiatives have seen the light. South Africa is partner to a number of these in collaboration with its neighbours such as Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and Swaziland and in the case of the Maloti Drakensberg Transfrontier Project, Lesotho.

THE MALOTI DRAKENSBERG TRANSFRONTIER PROJECT REVEALED

More than twenty years of continuous efforts between Lesotho and South Africa to have the protection of the mountain range shared by the two countries recognized culminated into the establishment of the Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Project. (MDTP, 2001) The initial project area constitutes an area of approximately 13 000km² straddling Lesotho and South Africa and is home to approximately 2 million people.

A Bilateral Memorandum of Understanding signed on 11 June 2001 by both countries shapes the institutional arrangements of the project and World Bank funding secured the first phase of implementation (2003-2007). A Bilateral Steering Committee oversees the MDTP internationally while Project Coordination Committees (PCC) consisting of different Implementing Agencies takes responsibility for managing the project in Lesotho and South Africa respectively. The roles and responsibilities of the Implementing Agencies of South Africa are contained in an Interagency Memorandum of Understanding signed on 3 December 2002.

The Implementing Agencies are constituted as follows:

- Lesotho: Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Culture (lead agent) and several other Ministries relevant to the project.

- South Africa: Department of Environment and Tourism (DEAT), South African National Parks (Golden Gate National Park – Freestate), Department of Tourism, Environment and, Economic Affairs (DTEEA - Freestate), eZemvelo KZN Wildlife (KwaZulu Natal), Department of Economic, Environment Affairs and Tourism (DEEAT – Eastern Cape), Eastern Cape Parks Board.

The project aims at conserving the unique natural and cultural heritage of the area and contributes to sustainable livelihoods by establishing a framework for collaboration between the two countries. A Project Coordination Unit (PCU) became operational in 2003 in both countries respectively and these multi-disciplinary teams are responsible to collaborate with Implementing Agencies on the processes linked to the following project components (MDTP 2001):

- Project management and transfrontier collaboration

- Bioregional/strategic planning

- Protected Area Management Planning

- Conservation Management inside and outside Protected Areas (Includes natural and cultural heritage)

- Community Involvement

- Sustainable Livelihoods and Eco-Tourism

- Institutional development

The scope of the project based on the link between environment and sustainability is extensive and even though the preparatory phase (pre-2001) was based on comprehensive consultative processes, the MDTP is an externally designed project that has the daunting task to intervene in existing processes in an attempt to affect transfrontier collaboration not only across international boundaries but also across institutional boundaries within each country.

THE MDTP AND ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION

One of the key objectives of the MDTP is to institute appropriate environmental education processes so as to enable a wide range of stakeholders to understand, engage with and act upon issues associated with biodiversity and cultural heritage. Faced with the same expectation as many other conservation and environmental education processes as to “get the message across” and not really knowing exactly what the message was, the MDTP - Note 1 - appointed a consortium consisting of environmental education specialists from Isikhungusethu Environmental Services (Pty) Ltd (IES) and the Wildlife Society of South Africa (WESSA) to collaborate with Implementing Agencies to develop an Environmental Education Programme appropriate for the transfrontier context.

The Challenges faced

The vision and objectives of the MDTP were broadly supported by the IES – WESSA team and it was noted that ‘process’ and ‘evolutionary growth in knowledge’ are key to the future of a program that is reliant on a diverse range of stakeholders. A few key challenges emerged that shaped the approach eventually adopted.

- Alignment of approaches (MDTP 2005a): The MDTP has a strong planning and project management approach (i.e. planning before doing) which assumed that once scientific, legal and planning process are completed and information is available, an education (didactic) approach can then be used to convey the message to the wider public. The IES-WESSA team based on experience in the southern African and Drakensberg region introduced a “plan as you do” approach to allow for learning. This challenged conventional thinking within the MDTP and introduced the team to the UNEP concept of “Open Process” that “moved beyond the simplistic transfer of knowledge as the basis of social change.” (Taylor 2006)

- Diversity of perceptions (MDTP 2005c): The number of stakeholders involved brought about a diversity of perceptions among different groups about what is appropriate action to protect the uniqueness of the mountain range. This posed the challenge to recognize and mobilize the prior knowledge of stakeholders to collaborate on a joint education program. Many existing processes and programs have been well researched, designed and planned for roll out; yet, many seemed not to succeed at implementation level due, primarily to a lack of meaningful, applied fieldwork and the mobilization of prior knowledge and understanding of local communities and wider stakeholder groups.

- Developing a mechanism/tool linking diverse resources to an array of activities and education outcomes: In response to the diversity of issues and stakeholders participating in the MDTP it was imperative that the education program and subsequent resource material transcended the geographical and institutional boundaries of the project by “developing something that brought everything together” (Personal communication, Sandra Taljaard, February 2007)

- Ensuring growth and sustainability of the program: The first phase of the MDTP concludes at the end of 2007 and the risk is there that the program could become static, unused and unresponsive in a changing environment, if not positioned as such that Implementing Agencies could participate in networking and international best practice processes to ensure that the program responds to the context of the project.

These four challenges primarily guided the approach and methodology adopted in the development of the MDTP Environmental Education Program.

The Approach and methodology adopted

Broad international trends in environmental education particularly in the context of the current United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainability (2005-2014) guided the realization in the MDTP that environment and sustainability issues are complex in that “they involve not only the biophysical environment but the interactions between the biophysical dimension and the political, social, technological, economic and aesthetic dimensions” (Taylor 2006). These complexities lead to different and often highly contested understanding of environmental issues and are particularly relevant in the context of the MDTP with its added dimension of transboundary collaboration. Even though these understandings change over time, there is increasing recognition that these different understandings are based not only on mistaken beliefs or lack of knowledge. Taylor concludes that they are often based on ‘different interests and cultural perspectives and represent rational decision making processes based on these interests.” (MDTP 2005b)

If environmental issues are complex and value laden and the understanding thereof shaped by different and often conflicting interests that are part of society, environmental education “needs to be critical and support learners [stakeholders] to deconstruct different understandings and the effects that they have in our lives.” (Taylor 2006). This challenges environmental education programs to be responsive to different contexts whilst enabling stakeholders with “reflexive skills that will enable them to think about and change the way that they learn and the kinds of information that they draw on as the situations around them changes.” (Taylor 2006)

The above views are supported in a publication (Lotz Sisitka, 2005) from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) where the following principles are suggested to influence curriculum design and capacity building processes in the field of environmental education and education for sustainable development:

- Responsiveness to the complex and changing social, environmental and economic context;

- Creating opportunities for participants to shape the content of the course;

- Open and flexible teaching and learning programs respond to individual participants needs.

- Recognition that within any practice there is a substantial amount of embedded theory and critically engage with this theory in different contexts.

- The above implies and supports reflexivity in terms of evaluating what we do, understanding why we do it in that way, considering alternatives and having the capacity to support meaningful social transformation when appropriate.

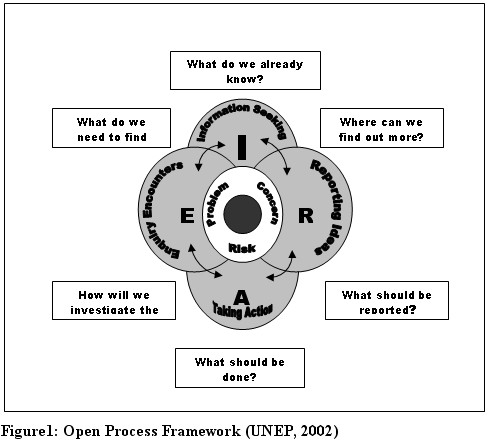

It is these principles that have informed more open processes of teaching and learning and it guided the MDTP’s approach to adopt the United Nation Environmental Program (UNEP) Open Process Framework (UNEP, 2002) as conceptual framework and approach for the development and implementation of its Environmental Education Program. The Open Process Framework is one way of representing learning and teaching processes that are responsive, flexible and participatory and within the complexities of the MDTP, this innovative approach supported a framework that seeks to:

- mobilize the prior knowledge and understanding that participants bring into teaching and learning situations;

- support the findings and critique of information;

- enables participants to question,

- explore and experiment in context;

- support the taking of meaningful action,

- report on learning processes in ways that lead to social change.

These processes are represented in the diagram below.

Following the Open Process Framework approach some of the key features of the associated methodology (MDTP, Inception report, June 2005, p2-3) adopted by the IES-WESSA Team included the following:

- Establishing the contextual profile of the user groups.

- Involving community-representatives (Learnerships) from selected areas along the Drakensberg in the environmental education program.

- Documenting issues relating to the biodiversity and cultural heritage of the region and ensuring that they are built into the environmental education materials.

- Developing a framework, strategy, materials and toolkit in the form of an environmental education program aimed at enabling community structures and Implementing Agencies to raise awareness and develop action about conservation and sustainable development in the project area.

- Development of related courses and training as part of the National Qualification Framework (NQF). Note 2

- Piloting the courses and materials with participants in three areas of the overall project area.

- Formulate the roll out of the environmental education program for the project area in collaboration with the Implementing Agencies

The IES-WESSA Team collaborated with the MDTP Environmental Education Task Team over a period of eighteen months to develop the program. This process included several sessions throughout the region ensuring that the Implementing Agencies as stated in the Inter-Agency Memorandum of Understanding were involved. Two non-governmental organizations; Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) and The Women Leadership and Training Program (WLTP) volunteered their services and played a significant part in contextualizing the program and subsequent resource material.

Key Findings and Outcomes

In response to the threat to the Maloti Drakensberg mountain range as a unique regional resource that is fundamental to the livelihoods of local residents, the Environmental Education program has been identified as one of the opportunities for different user groups (with differing values and interests in the resources) to be brought together. Under the leadership of the IES-WESSA team collaborative efforts between many stakeholders culminated in four major outcomes:

Understanding the status quo and stakeholder analysis

Substantial research brought about an understanding of the nature and extent of environmental education resources, programs and processes as well as the diversity of perceptions existing in the region. It was clear that the MDTP Environmental Education Program had to provide a program that supported established programs particularly as it related to the Implementing Agencies whilst ensuring that the transfrontier context of the region was reflected in resources and supporting processes. The development of the subsequent program and resources were based on this conclusion.

Materials Development

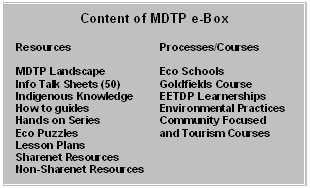

Early on in the process it was identified that extensive material existed in the region and that a large number of agencies provided training and it was decided that it would be duplication to develop further material for an already saturated market. An alternative approach was followed and it was decided to develop the “e-Box” toolkit which could be used to open up the issues confronting the region at all levels and among all groups in the region. The aim of the e-Box is to introduce interest groups to the diverse issues which have been identified as to be addressed in order to achieve sustainability of the biodiversity of the region. This is achieved by means of what is termed a “picture building landscape activity/enviro picture” where these issues are identified and participants collectively find solutions to the issues. In finding solutions experience suggests that they also find one another in terms of mutual understanding and shared learning experiences. Multiple support materials are included in the e-Box or referenced for those needing further information with linkages to accredited and non-accredited training courses.

The e-Box and in particular the landscape activity/enviro-picture effectively became the mechanism that linked diverse resources to an array of activities and education outcomes and succeeded in “developing something that brought everything together”.

MDTP Training Plan

Based on the aforementioned outcomes the MDTP in collaboration with its Implementing Agencies is rolling out a training program in support of the Environmental Education program with the aim to build capacity throughout the region to ensure support for Phase 2 of the MDTP (2008-2012).

The training program supports the following:

- Environmental Education, Training and Development Practice (EETDP) Learnership NQF Level 6: 31 learners

- Schools and Sustainability Course in support of Eco Schools: 15

Educators

- Short Courses in Community Conservation, Tourism Management and Cultural Heritage Management: 75 Learners

Ensuring sustainability

The need for a regional centre to continually update and renew environmental education resources was identified early on in this project. WESSA working in partnership with the University of KwaZulu-Natal and Rhodes University submitted an application to UNESCO for recognition as a Regional Centre of Expertise (RCE). The RCE will serve a platform for dialogue and coordinated action amongst participating organization in the RCE. The MDTP supported this application as a regional partner with the aim to enable its Implementing Agencies to participate in a regional and international network that could support and sustain the Environmental Education program through the next phase of the MDTP and beyond.

Conclusion

A large-scale project such as the MDTP is prone to remain stuck in its own rationales as it remains involved with externally mediated planning frameworks and objective decision making orientations. The open process framework approach adopted in the development of the environmental education program allowed for an invaluable experience in what is referred to as “intangible human shaping processes” (Taylor, 1997, p 180).

Not only did this process improve communication between individuals and organizations in the different disciplines involved in the region, it also led to the recognition that ‘silos’ need to be broken down in the interest of effective management practices.

The open process framework approach managed to mobilize prior knowledge by providing participants the opportunity to develop resources appropriate for their situation. It addressed the challenges faced by transboundary conservation effectively and although the two countries’ programs developed separately, the communication link between the professional teams involved, ensured that information was shared leading to the programs supporting each other.

The most important lesson learned in this process can be summarized as: “It is important that our passion for change and ‘quick fixes’ doesn’t blind us to building better relationships, being responsive to issues and risks as they arise and most importantly working together and learning to ask better, more informed questions.” (MDTP 2005)

REFERENCES

Lotz-Sisitka, H. (2005). Developing Curriculum Frameworks: A Source

Book on Environmental Education among Adult Learners. Sharenet.

Howick.

MDTP (2001). Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation and Development Project Implementation Plan. South Africa. pp1-7, 22-24.

MDTP (2005a). Development of an Effective Environmental Education Program for the MDTP, South Africa. Inception Report, IES-WESSA. Howick. pp 2-5

MDTP (2005b). Maloti-Drakensberg Environmental Education Program. Combined Status Quo and Stakeholder Reports. Working Document. IES-WESSA. Howick. p 3, 5

MDTP (2005c). Maloti-Drakensberg Environmental Education Program. Combined Status Quo and Stakeholder Reports. Final Report. IES-WESSA. Howick. p 7.

MDTP (2006). Close Out Report for the Maloti-Drakensberg Environmental Education Program. IES-WESSA. Howick. pp 4, 7-8, 15-16, 19-20.

Taylor, J (2006). International Best Practice: Environmental Education Processes. Personal Notes. Howick. pp 1-4.

Taylor, J (1997). Share-Net: A Case Study of Environmental Education Resource Material Development in a Risk Society. Share-Net. Howick. p 180.

UNEP (2002). Action Learning, UNEP. Nairobi.

Note 1 - Although this paper focuses on the South African Environmental Education Programme it must be recognized that a similar process ensued in Lesotho and through coordination between the professional teams (WESSA and IES) and their counterparts in Lesotho, significant synergy was created between the respective programmes. The issues and contexts of both countries were considered in relation to each other and allowed for parallel programmes to be developed without impeding the sovereignty of both countries.

Commento

© 2016 Creato da Massimo.

Tecnologia![]()

Devi essere membro di Green leaves per aggiungere commenti!

Partecipa a Green leaves